Hypothyroidism: Understanding thyroid function and knowing what to test for

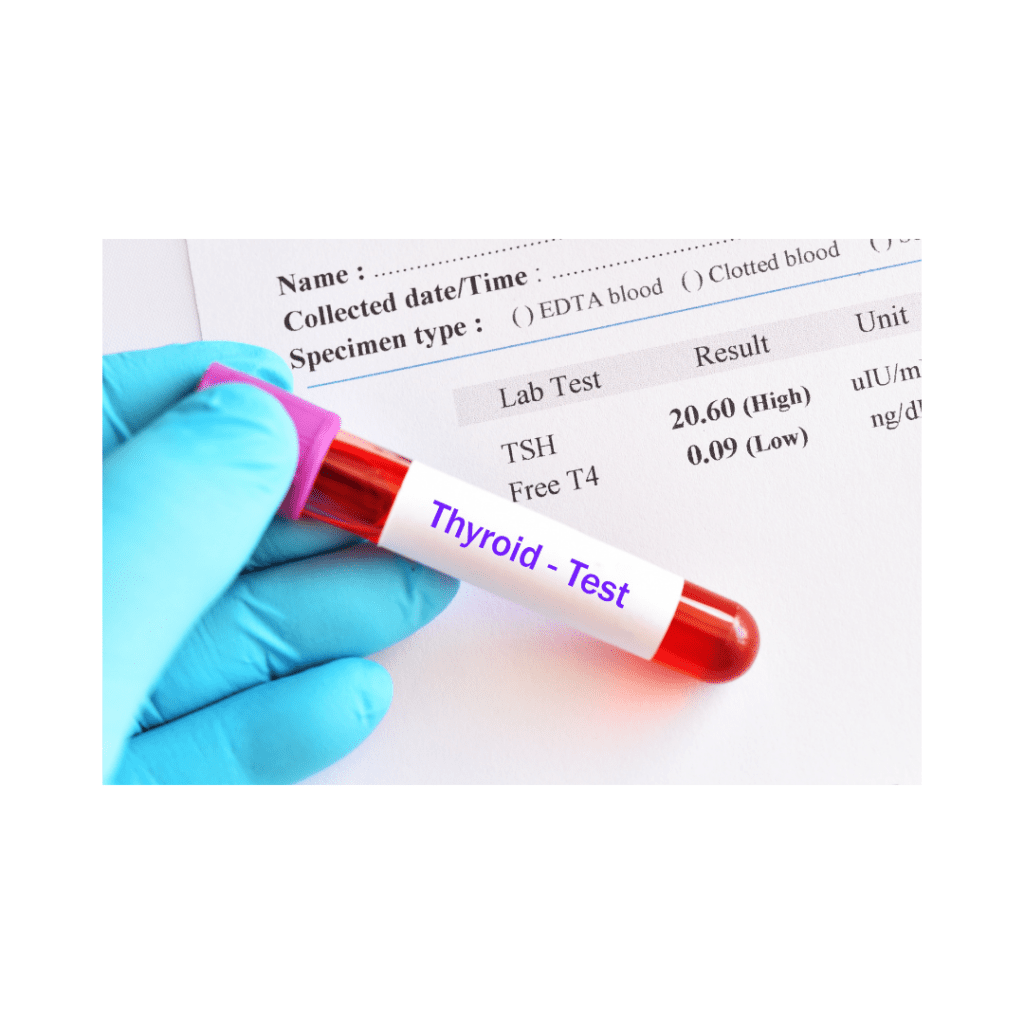

Do you experience extreme fatigue? Are you putting on excess weight? Are you always freezing? It could be due to hypothyroidism. Often physicians only check TSH and T4 but there is more to the thyroid story. I always recommend my clients get a full thyroid panel to rule out subclinical hypothyroid or an autoimmune thyroid condition called Hashimoto’s. I have included the markers to check along with their indication in the diagnosis of hypothyroid and their functional ranges.

Hypothyroidism is an underactive thyroid gland, or reduced stimulation of the thyroid receptors. There are three types of hypothyroid conditions.

Overt hypothyroidism where there is an increased TSH and decreased T4 level.

Subclinical hypothyroidism (SCH) is a mild form of hypothyroidism where there is only an abnormal TSH level (mildly elevated) but T4 is within normal limits. That is why it’s critical to not only measure T4 but also measure T3 in these cases. Often individuals present with clinical symptoms of hypothyroidism in SCH with fatigue, weight gain, cold intolerance, and mood disturbances.

Hashimoto’s thyroiditis is an autoimmune disease, in which the body produces antibodies that attack the thyroid gland. Hashimoto’s often presents with other chronic conditions including GERD, nutritional deficiencies, anemia, adrenal insufficiency/fatigue, intestinal permeability/” leaky gut”, along with classic hypothyroid symptoms. Additional testing may be of benefit which include food sensitivity testing, GI stool analysis, and an adrenal assessment.

I recommend a full thyroid panel when investing hypothyroidism which include fT3, rT3, Thyroid antibodies: TPO, TGB Ab & TSI along with standard fT4 and TSH.

TSH (Thyroid-Stimulating Hormone) Is produced in the pituitary gland and stimulates the production of T4 (thyroxine) which gets converted to the active form T3 (triiodothyronine).

Functional ranges for adults: 0.3-5 uIU/mL (a little larger range than conventional values)

TSH is usually elevated in overt hypothyroidism and may be mildly elevated in SCH.

Low levels may be indicative of secondary hypOthyroidism (pituitary or hypothalamus dysfunction): Diseases of the hypothalamus diminish the capability of the hypothalamus to secrete TRH (thyrotropin-releasing hormone), which is a major factor that determines TSH production and secretion. Diseases of the pituitary diminish pituitary production of TSH. 1 (pg. 486-488)

Also, to note elevated cortisol levels (due to increased stress) can suppress TSH, showing within range.

T4, Free (Thyroxine)

T4 is made in the thyroid gland and accounts for more than 80% of the thyroid glands production. T4 is considered a prohormone as it requires conversion to the active form of T3.

Eighty percent of T4 is converted to T3 in the liver and kidneys, while 20% T4 is converted to T3 via the GI tract. Therefore, compromised health of the liver, kidneys, or GI tract could lead to impaired thyroid conversion and activity.

Functional range: 0.8-2.8 ng/dL 1 (pg. 497)

*T3, Free (Triiodothyronine)

T3 is 5 times mor active than that T4. It can be low due to reduced conversion of T4 to T3. Thyroid hormone receptors respond only to T3, thus if there is a lack of conversion from T4 to T3, there is low thyroid stimulation and low thyroid activity leading to hypothyroidism. Therefore, the monitoring of T3 is especially important if clinical symptoms point to low thyroid.

Functional ranges may consider this in the upper range of normal and may be indicative of acute inflammatory stages of thyroiditis (inflammation of the thyroid) or Hashimoto’s. The thyroid secretes increased T3 levels during the acute inflammatory stages of thyroiditis. 1 (pg. 506-507)

Range: 2.0-4.4 pg/mL

Reverse T3 (rT3)

The body also converts T4 into rT3, which is 3,3´5´-triiodothyronine, an inactive form of T3 that is incapable of the metabolic activity that is normally carried out by T3.

T4 is converted to 50% T3 and 50% rT3. T3 and rT3 serve as their own checks and balance. Too much stimulation of T3 will convert any excess T3 to rT3.

It is believed that the body produces rT3 in times of severe illness or starvation as a mechanism for preserving energy. Stress can also increase rT3.

Range: 9.2-24.1 ng/dL

Thyroid antibodies are usually present in Hashimoto’s thyroiditis, also known as autoimmune thyroiditis. Where the immune system attacks its own thyroid, resulting in chronic inflammation and the thyroid becomes damaged overtime and cannot produce enough thyroid hormones.

*Thyroid Ab (TPO – thyroid peroxidase antibody)

This is a thyroid antibody – functional ranges indicate a titer level < 9 IU/mL

TPO Ab are immune cells that indicate the immune system is attacking TPO in the thyroid gland. The TPO Ab test is the most important, because TPO is the enzyme responsible for the production of thyroid hormones, (conversion of T4 to the active form T3) and the most frequent target of attack in Hashimoto’s. (2)

This is detectable due to chronic thyroiditis (Hashimoto’s thyroiditis): Antimicrosomal antibodies attack the microsome in the thyroid cells. The immune complex creates an inflammatory and destructive process (due to gluten, dairy, and other inflammatory environmental factors) of the gland, which is mediated through the complement system. 1 (pg. 104-105)

*Thyroglobulin Antibody (TGB Ab) This is detectable in Hashimoto’s thyroiditis: Antithyroglobulin antibodies attack the globulin (protein structure) in the thyroid cells. The immune complex creates an inflammatory and destructive process (due to gluten, dairy, and other inflammatory environmental factors) of the gland, which is mediated through the complement system. 1 (pg. 102-103)

TGB Ab are immune cells that indicate the immune system is attacking thyroglobulin in the thyroid gland. Sometimes this test is necessary as well because it is the second most common target for Hashimoto’s disease. (2)

TGB Ab < 116 IU/mL

*TSI (Thyroid Stimulating Immunoglobulins)

If this is detectable, it just verifies Hashimoto’s thyroiditis. TSI represent a group of immunoglobulin-G (IgG) antibodies (these show up in autoimmune disorders, again brought on by an inflammatory state due to leaky gut due to gluten, dairy, etc.) directed against the thyroid cell receptor for thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) and are associated with autoimmune thyroid disease i.e., Hashimoto’s. This instigates stimulation of the thyroid gland independent of the normal feedback-regulated thyroid-stimulating (TSH) stimulation. In turn stimulating the release of thyroid hormones form the thyroid cells. 1 (pg. 491).

TSI < 130% of basal activity

Hashimoto’s and Gluten Sensitivity

Regarding Hashimoto’s thyroiditis and its link to leaky gut and gluten sensitivity. The balance between immunity and tolerance is necessary for a healthy gut. Abnormal immune responses to environmental triggers/antigens such as certain microbes and possibly gluten in genetically susceptible individuals can lead to an influx of inflammatory/immune cells. Which leads to altered epithelial tight junctions within the GI tract, increasing permeability triggering autoimmune thyroiditis (Hashimoto’s). Leading to continued influx of antigens into the bloodstream with continued immune response targeting the thyroid gland. So, it’s not only important to identify and remove environmental triggers (i.e., gluten) but also to restore the intestinal barrier with supplements such as glutamine and probiotics.3

* Levels that should be drawn with Hashimoto’s Thyroiditis.

- Pagana KD, Pagana TJ. Mosby’s Manual of Diagnostic and Laboratory Tests. 5th Ed. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier; 2014.

- Mahan LK, Raymond JL. Krause’s Food & The Nutrition Care Process. 14th Ed. Louis, MO: Elsevier; 2017.

- Kohlstadt I, ed. Advancing Medicine with Food and Nutrients. 2nd Ed. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press; 2012.